In May of 2010, my first week in Singapore, my manager PB* gave me a friendly warning about communication in Asia. “Be indirect,” he said. I have been pondering that thought and occasionally writing about it for a year and a half. A couple weeks ago PB sat down with me to discuss a variety of aspects of my first Asian tour. He again kindly and firmly repeating his warning: be indirect.

We all have good days and bad days with email. In the same week my boss gave me this friendly nudge, a colleague of mine complemented my patient and kind emails. PB has much more experience in Asian business than this colleague and I put together. But I could not figure out how one person could think I was writing well while the more Asian-savvy PB saw room for improvement. So I started to mull over what I might be missing.

On this week’s plane flight to Sydney I developed a lead in this mystery. I heard a common flight warning and connected a strange characteristic of Singaporean English with PB’s advice. I had been laughing to myself about this weird facet of the local English. But now I realize it is likely deliberate and not something to laugh at.

Consider the following common Singaporean instructions. On this week’s plane flight, Singapore Airlines attendants said, “Seat belts should be put on, babies should be put in the bassinet.” This sign warns pedestrians of construction all around Singapore:

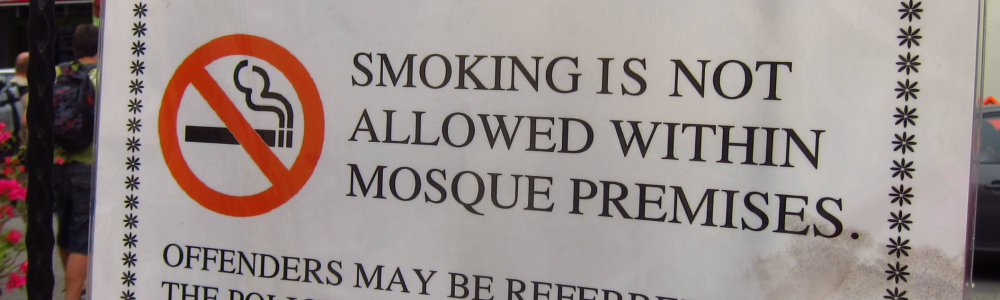

Some smoking signs display the same characteristic grammar:

And the Singaporean Ministry of Manner provides a bonanza of this language, which I found after about three seconds of research:

A factory is any premise which any of the following is carried out:

- the making of any article or part of any article;

- the altering, repairing, ornamenting, finishing, cleaning or washing of any article;

- the breaking up or demolition of any article;

- the adapting for sale of any article.

If you are a writer you may have already noticed the common quality of all these sentences. They are all in passive voice. The subject is omitted and vague. But in indirect languages, which are dominant in Asia, vagueness is intended. The reader is accustomed to the omission and easily deduces the subject.

For most English writing passive voice is considered bad writing. There are notable exceptions like technical journals. But most American readers–perhaps most English readers–prefer reading sentences with explicit subjects and powerful verbs. But Singaporeans frequently use passive voice in English communication, where commands are not pushy and directed at the reader.

I have a theory that my communication style contains too much active voice. Since I started my hobbyist efforts at improving my writing about five years ago, I have striven to purge passive voice. The result is a style that is radically different from the above. I would write, for instance:

- Put on your seat belt (not “seat belts must be put on”)

- Do not smoke within mosque premises (not “smoking is not allowed within mosque premises”)

- A factory is any premise that makes any article or a part of any article (not “A factory is any premise which any of the following is carried out: the making of any article or part of any article”)

I prefer my own version because it is direct and has more power than the Singaporean version. But I realize a Singaporean might consider my direct version rude. If I am right, I have to develop my passive language skills to improve my written communication in southeast Asia.

I now have a theory and my entire life to experiment with it. PB’s advice a couple weeks ago was that I further develop my skills of indirect communication. I will play with passive voice in emails and gauge the reactions of my colleagues in the coming months.

(*) If you know my manager, you know what PB stands for. If don’t, I’m declining to add his name to the blogosphere without his permission.